Friday I was at the Concord Museum for a visit and got a call to pick up a New England fowling piece I had last seen in 2008. I brought it home and decided I would write my next blog post about it as it was so nice and made in 1774 by a doctor from Sudbury, Massachusetts. It’s such a beautiful small-bore gun that I decided to post it on my facebook page and a few hours later someone posted with a question, “how many towns had gunsmiths in the years preceding the war?” I answered the question very briefly and after thinking about what she had asked for a bit, my idea for the blog changed.

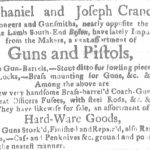

Nobody really knows how many gunsmiths there were during this time. And were they making all the parts from scratch? The answer is not many were making the barrels and locks. These parts took a lot of time to make and prior to the war were readily available for purchase from shops in Boston, Providence, and other cities. Most of the guns being built were made from imported locks and barrels and were stocked here. Not that there isn’t skill needed to build guns, there was, but by having the parts available, men who were good working with metal and wood could assemble guns and sell them to those that couldn’t make them. You also didn’t need a large shop if you were assembling guns and not making the parts that needed more tooling. For instance, barrels at the time were made from flat stock that was wrapped around a mandril and hammered into shape with the seam welded together. The barrel was then smoothed and bored. This took a lot of time, skill, and equipment to make properly. You also had to make sure that the gun could be proofed without exploding and hurting or killing the shooter. Making locks was also finicky. All of the parts had to be installed just right for it to function properly. Why go to all of this work when you could purchase the items ready-made?

Sometimes we see names of men like Samuel Hartwell from Lincoln, Massachusetts. He is listed as a clock maker and a gun maker. Clocks were made in a similar manner. The movements and parts were imported, and the clock maker would build the case, put his name on it, and sell it.

In 1774, the British government placed an embargo on the colonies and as the war broke out, the supply of guns and parts dried up. Men who could build guns were using older locks and barrels scavenged from beat up guns to build into new. It wasn’t until the summer of 1777 when French muskets and gun locks were being imported in bulk that the problem of getting guns, barrels, and locks changed. You have to remember that by law, all males from 16 to 60 had to be in the militia and “armed and equipped according to law,” so guns were not just a necessity for hunting, but your duty to own one for your militia service.